Mendini called himself "a novelist who writes on objects". His love of literature was immense and his Proust Chair, one of his most famous designs, is an ode to Marcel Proust, inventor of the modern novel. The armchair with baroque curls is hand-painted with a pointillistic landscape à la Paul Signac, a contemporary of artist Proust. In 2015, Magis produced a plastic version of the chair.

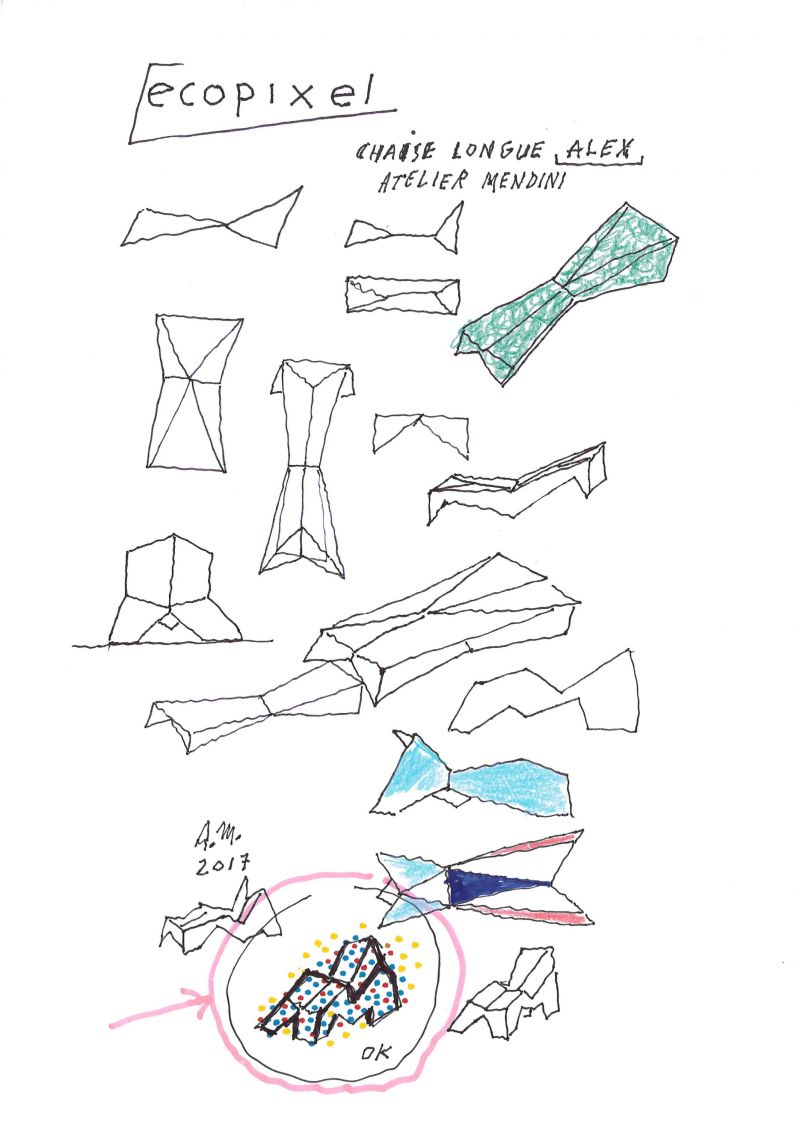

As an innovator in the field of material use, Mendini entered into a partnership in 2017 with the plastic manufacturer Ecopixel. He had tiles made up mostly of recycled polyethylene in eight colours and 2.4 centimeters square. He mixed and melted them, then pressed them into the shape of a chaise longue. Each copy has a unique pattern. And they are all recyclable.